The 4 Best SaaS Pricing Strategies Based on Psychology

Developing an efficient SaaS pricing strategy is essential to succeeding as a business. However, this involves far more than simply deciding how much your plans costs. Price optimization is an essential part of your SaaS pricing strategy, and can make the difference between growth and stagnation.

So, how do you arrange your plans to highlight their value? And how can you direct customers towards the most profitable choices?

This is an introduction to price optimization

But first, here is a story from my own life to illustrate how important pricing can be…

Price Optimization and Psychological Pricing – a digest

Some years ago I met a friend of mine, Roberto, who runs an Italian restaurant in Munich. The restaurant has a beautiful ‘trattoria’ ambience, serves delicious food, and offers a fantastic selection of Italian wines. It is a wonderful place to spend an evening and always promised to be a successful business. But there was a problem.

Roberto’s restaurant had a small seating area, which led to an enormous waiting list. In fact, he regularly had to turn customers away. Despite the demand for his food, Roberto was unwilling to increase his prices. Because of the lack of space He was also unable to increase his sales. What he needed was for his customers to start trying more expensive dishes.

After some research, Roberto discovered the work of Aaron Allen, a Psychological Pricing consultant who specialises in menu profitability. Using Allen’s ideas, Roberto restructured his menu.

- Although he retained his previous prices, he repositioned the options so that they were no longer in order of cost.

- The first item in each category was now the most expensive option.

- He introduced new ‘price anchor’ items (for example, a €297 bottle of Barbaresco wine.)

I have been writing about the impact that cognitive biases have on consumer behaviour for a number of years. Even so, the impact of these simple changes left me stunned…

The revenue generated by Roberto’s menu grew by over 20% (I can’t say exactly how much, for reasons of confidentiality, but I can tell you that I was amazed…)

To achieve the same result, Roberto would have had to increase his prices or his restaurant’s seating area by the same proportion (more than 20%). Instead, he introduced a couple of extra lines to his menu. His revenue rose simply because his clients chose, on average, a more expensive dish or wine.

Price Optimization Tactics

Roberto’s menu strategy was based on the principle of Decoy Pricing. When positioned alongside an extravagant option, a moderately priced item looks like great value. The technique is used in a number of industries to encourage higher-value purchases

However, this is not the only psychological principle applied by SaaS businesses to optimize their SaaS pricing strategies. Using cognitive biases such as ‘anchoring’ and the ‘serial position effect’, any business can add value to their offerings. Here is a list of Price Optimization techniques that use psychological pricing to increase revenue:

The Anchoring Effect and Price Optimization

The anchoring effect describes our tendency to focus on the first piece of information we receive when evaluating subsequent information. Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman described the phenomenon in their 1973 paper ‘Judgement under Uncertainty’ and it has become a familiar part of SaaS pricing strategies.

Remarkably, the first piece of information we receive does not even need to be relevant to the decision we are making in order to affect the result. In his Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely describes an experiment in which students are asked to bid on items after having written down the last two digits of their own Social Security number.

The amount they were willing to bid differed by up to 346%, depending on how high these unrelated numbers were.

Anchoring as a SaaS Pricing Strategy

Discount offers in retail stores provide a good illustration of how anchoring can enhance a product’s perceived value. By suggesting a RRP (regular retail price), and then offering a reduced rate, stores present customers with seemingly irresistible offers. The effect works regardless of how reasonable the unreduced price is.

The first number you provide clients with will be used to evaluate subsequent information. Priming potential customers with large numbers is proven to increase the perceived value of your offers. You can do this with a now-defunct high-cost offer, an entirely unrelated number, or by sorting your offers in descending price order.

Decoy Pricing, or, ‘The Ugly Brother Effect’

Decoy Pricing is similar to the Anchoring Effect, in that it appeals to our tendency to use comparison to judge value. The Decoy Effect enhances the perceived value of an offer by presenting it alongside a disproportionately expensive item.

The case of Williams-Sonoma in the early 90s has become a classic in marketing and persuasion books. Williams-Sonoma, a small appliance manufacturer, once introduced a $275 bread maker to its range. They soon encountered a problem… Despite the fact that the other products of Williams were selling well, the sales of this bread machine remained well below expectations.

With the help of a marketing consultant, the company had an idea. Williams-Sonoma introduced in its range a second bread machine, slightly larger, but with a much higher price ($429).

As a result, sales of the $275 machine nearly doubled.

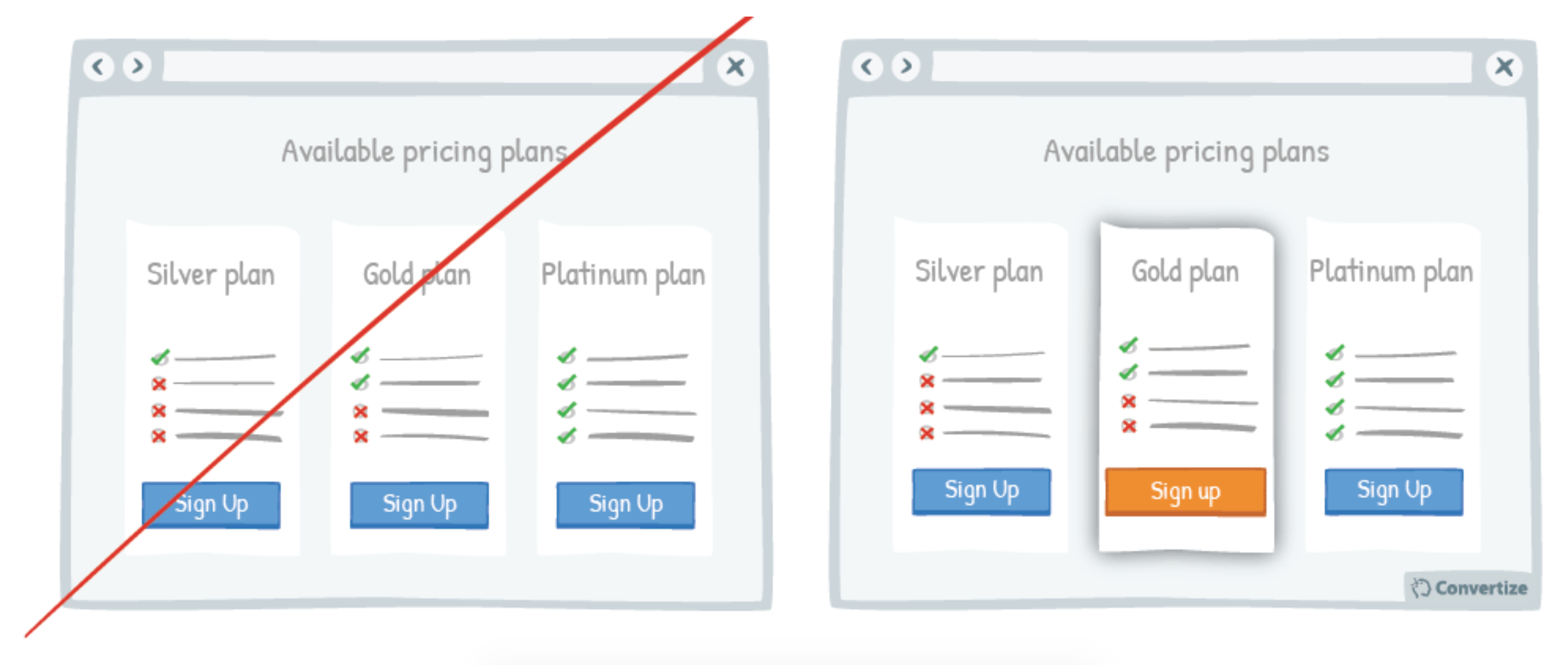

Decoy Pricing as a SaaS Pricing Strategy

Most software services provide a range of packages for different customers. In this old pricing scheme, Crazy Egg (a provider of heat-mapping software) list their offers in descending price order.

Crazy Egg position their most expensive offer (“Pro”) first. They use it as the less attractive offer (known as an “A-” offer). Next to it is the package that Crazy Egg wants to sell to its customers (known as the “A” offer). “Plus” is disproportionately attractive, and highlighted as the most popular choice.

Crazy Egg’s goal is to prevent the visitor from choosing the Standard or Basic offer (even though competitors offer solutions at these prices).

By carefully arranging the names and features assigned to their packages (“Pro” and “Plus” establishes an immediate comparison, whilst “Standard” and “Basic” are easily ignored) Crazy Egg guides the consumer in making their decision.

Decoy Pricing Can Increase Revenue by 42.8%

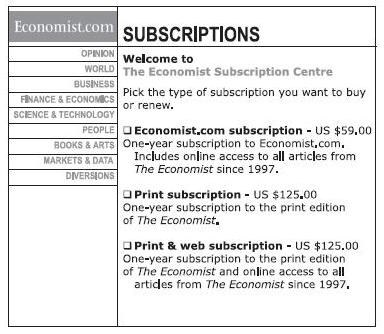

Dani Ariely highlights another example of Price Optimization in his Predictably Irrational. One day, he stumbled upon this online ad by The Economist.

The Economist was offering a ‘Print Subscription’ for the same price as a ‘Print & Web Subscription,’ with both costing $125. But why would The Economist advertise a more comprehensive offer at the same price as an inferior option?

Ariely set up a study with a representative sample of students and asked them what they would choose. The outcome was remarkable:

- 16% chose the ‘Online Subscription’

- 0% chose the ‘Print Subscription’

- 84% chose the ‘Print & Web Subscription’

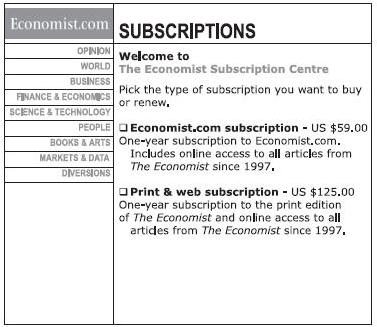

It seemed as though the unattractive ‘Print Subscription’ offer was increasing the desirability of the ‘Print & Web’ offer. In order to test this, Ariely presented a different group of students with the following offering:

He simply deleted the option that nobody in the previous group had chosen… guess what happened:

- 68% chose the ‘Online Subscription’

- 32% chose the ‘Print & Web Subscription’

In other words, adding an option that nobody wanted was essential to the magazine’s pricing strategy. The decoy increased revenue by 42.8%

Position and Price Optimization

Over the past 50 years, cognitive psychologists have conducted significant research on the effect visual positioning has on sales. They have identified two price optimization phenomena as being particularly significant: The Serial Position Effect and The Centre Stage Effect.

Serial Position Effect

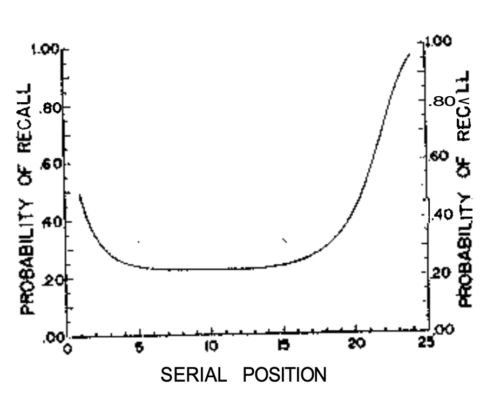

The Serial Position Effect describes the way in which information presented in a series is recalled. People are most likely to remember items given at the start of a list (this is called Primacy) and those at the end (this is labelled Recency). However, subjects struggled to remember items given in the middle of a list.

The effect occurs because the largest amount of cerebral processing is devoted to the first pieces of information we receive. At the same time, the last few items are maintained in our short-term memory. A study using word lists, conducted at the University of Vermont in 1962, demonstrated the tendency of participants to recall words at the beginning and end of a list.

The Serial Position Effect has important consequences for all forms of communication. For example, the position of advertisements or links on a webpage has a significant effect on their value. A study conducted at the University of Western Australia in 2006 showed that items at the top and bottom of a webpage receive many times more clicks than those on the rest of the page.

As my friend Roberto found out, the same principle is often employed when designing menus. Restaurants often place dishes with the highest margins at the top of a category, as these are the most likely to be chosen by a customer. They often arrange wine lists so that the first, second, and final wines are those with the highest margins.

Centre Stage Effect

When presented with a limited range of choices, most people are drawn towards items positioned in the centre. In 2012, Rodway, Schepman and Lambert (2012) conducted a series of studies demonstrating the effect of the phenomenon in a variety of contexts. Whether the line-up is vertical or horizontal, involving real-life products or online images, the effect still seems to hold true.

The effect has numerous applications. For example, online marketplaces such as Amazon and Ebay are able to charge higher rates for advertising slots in the centre of a series. For pricing plans, it suggests that a list of three or four packages should be arranged so that the ‘A’ offer is near the centre.

The Paradox of Choice and SaaS Pricing

When presented with an overwhelming range of products to choose from, most customers will end up deferring their purchase. An fMRI imaging study conducted at the University of Minnesota in 2008 showed that brain activity during a difficult decision mirrored that of a subject experiencing physical pain. Equally, comparing similar products with clear and simple differences produced feelings of pleasure.

In his 2004 book The Paradox of Choice, psychologist Barry Schwarz showed how, instead of increasing our capacity to make a decision, an abundance of choice can lead to anxiety and dissatisfaction. Even though we imagine we would be happier with more choice in our lives, we are usually happier when fewer options are presented to us.

In order to avoid the problem of the Paradox of Choice, it is usually best to avoid offering an excessive number of options.

Applying the Paradox of Choice to Price Optimization

Take, for example, a smart ageing company (that can help you to reduce the speed of your cellular ageing) offering 2 programmes:

- a one-to-one coaching program with an ageing expert $97

- a comprehensive package including a cellular ageing test, 12 months supply of specific anti-ageing supplements, and access to online content $497

These options are so different that our brain has difficulty comparing them. Even if the objective “Better Ageing” is addressed by both, it is impossible to say whether we would benefit more from personalised coaching or cellular ageing tests. The chances are, we will choose neither.

If, however we are presented with more directly comparable options, our choice will be far easier. Imagine, for example:

- a cellular ageing test $97

- a comprehensive package including 12-months of anti-ageing-supplements and a cellular ageing test $297

- a comprehensive package including 12-months of anti-ageing-supplements and two cellular ageing tests (one before and one to be used after 12 months) $307.

In the latter example, the cognitive friction exerted on our brain is much less as the options are easier to compare. Presenting the choices like this reduces the experience of paralysis that comes with too much choice and increases the likelihood that we will make a purchase.

Conclusion

Most consumers make judgements through direct comparison. By understanding how this process works, you can optimize your SaaS pricing accordingly:

- Increase your average customer value without changing your prices

- Convert indecision into decision more often

- Enhance your conversion rates

When thinking about how to optimize your SaaS pricing, test the introduction a decoy offer next to the offer you want to sell first. Make sure that your decoy offer is slightly less attractive than the offer you want to sell (more expensive, or at the same price but with less attractive features).

On the web, this tactic works best if you offer between 2 and 4 plans next to each other on the page.

To propel sales of a plan that is difficult to compare with others in your offering, introduce a second option that is easy to compare but less attractive.

Our library contains 70 tactics for optimizing your pricing page, and is free to browse. Alternatively, explore the full range of cognitive biases involved in consumer behaviour. For more SaaS insights, browse our collection of expert Web Marketing articles.